Racial hostility plagues CV

Oct 22, 2015

“I didn’t think it would be a problem … But then I come here and there are people that don’t like black people, and I’m not used to that,” said Alexis Tellis, freshman biochemistry major and chair of public relations for the Black Student Union (BSU).

A recent report by 24/7 Wall St., published in the Huffington Post, named Waterloo-Cedar Falls the 10th-worst place for black Americans to live in the United States. The report used an index of eight measures to compare differences between white and black populations in metropolitan areas.

Tellis, who grew up in Des Moines, said that her experience there with race was generally positive and that, regardless of race, most people seemed to get along.

However, that all changed, she said, when she came to Cedar Falls for college.

Des Moines also made the list. All cities mentioned were in the Midwest.

Some of The Cedar Valley’s determining factors were the median household income — African Americans in the area make 56 percent of their white counterparts — and the unemployment rate. The Cedar Valley had the highest black unemployment rate on the list at 24 percent, compared to a four percent white unemployment rate in the area. The report used available data from the 2014 Census Bureau to determine these results.

Methodology disputed

“When you go through the report, it’s a very interesting title,” said Hansen Breitling, director of diversity and student life. “But to say something like, ‘worst city’[…] it’s a very large and complex question to try and be answering. So it’s absolutely oversimplified.”

Breitling had concerns with the report’s methodology. He said that to make a qualitative statement — deeming an area the “worst place for black Americans” — the study must also look at qualitative data. For Breitling, the report’s use of an eight-measure index was too narrow.

However, he did say it was cause for concern.

“The numbers are totally significant,” Breitling said. “[But the study itself] is not something I’d want students to be worried about when coming here on campus.”

Personal experiences

As a member of BSU, Tellis said that a recent incident occurred in which a roommate told her that BSU’s performance at the Homecoming Pride Cry was “exactly what she expected to see from black people.”

“That made me uncomfortable,” Tellis said, and she immediately moved out and has been staying with a friend.

“[The DOR] found me a new roommate,” Tellis said. “And so I went yesterday to talk to [my old roommate], and, long story short, she just flat out told me: ‘I don’t like black people, and I don’t want a black roommate.’ So I had a breakdown last night.”

Jada Jackson, sophomore social work major and president of BSU, said that microaggressions, rather than explicit racism, are much more common on campus.

Jackson said she was once a member of a group presentation where she was told to “carry her own weight,” implying that she, the lone black student, wasn’t capable.

Jackson is from Gary, IN, a city with a high black population. She said that, when she came to UNI, she immediately felt like an outsider, because Cedar Falls is significantly less diverse. For Jackson, this feeling of isolation was furthered by racist posts on Yik Yak regarding UNI’s minority students.

“I was like, ‘Okay, I guess they don’t really care for us here,’” Jackson said in regards to the Yik Yak posts.

Action needed

Carissa Froyum, professor of sociology at UNI, said the report should be seen as a call-to-action.

“This is what the reality is, and we have a moral obligation to do something about it,” said Froyum, whose emphasis is in social inequality.

Like Breitling, Froyum said that, while the qualitative claims made by the report can be disputed, the numbers are significant. She said that disparities in unemployment and income are important, but the report also ignored a factor of equal importance: segregation.

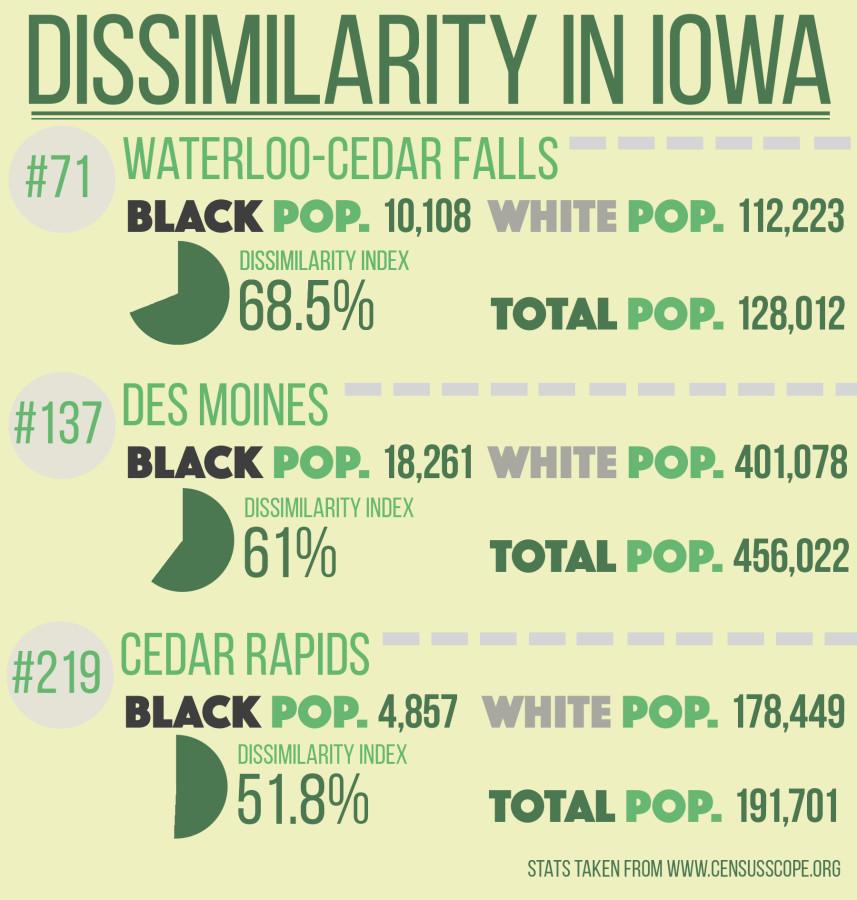

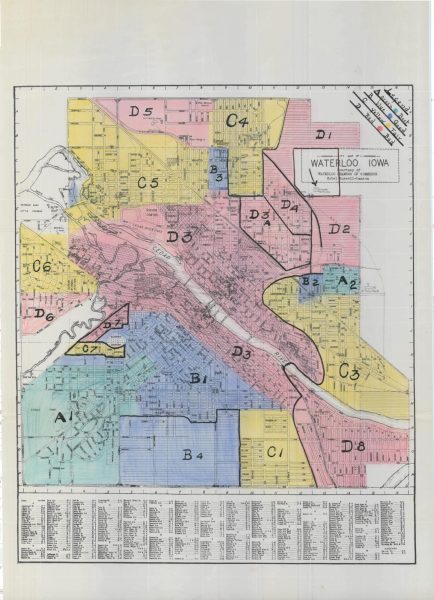

The dissimilarity index, a measure of segregation in a given area of at least 1,000 residents and a significant minority population, shows that The Cedar Valley has a dissimilarity index of 68.5, according to censusscope.org. An index score greater than 60 is considered a high level of segregation.

Segregation growing

Gary, IN, Jackson’s home city, tops the list in the U.S. with a dissimilarity index of 87.9.

According to Froyum, since 1980, there has been a trend toward more segregation in the U.S. in the workplace and at home.

“If white folks will only buy houses in white, Cedar Falls neighborhoods,” Froyum said, “we as a community of white people need to think real seriously about what we’re doing.”

As far as combatting racism at an individual level, Jackson feels there’s only so much that can be done.

“We can’t really change how someone thinks or how they were raised. It’s impossible, really,” Jackson said.

Froyum said that change must occur systematically as well.

“What the research shows is that in order for racial change to actually happen you have to have accountability structures within the institution,” Froyum said. She said certain individuals or committees must be designated to create change, have the power to do so and be accountable for making that change.

She also emphasized localized interaction.

“It’s not diversity training that creates change; it’s individual contact with people who are different from yourself — repeatedly, over and over,” Froyum said.

Local action needed

Froyum and Breitling agreed that the UNI community needs to be engaged more broadly with the entire Cedar Valley.

“I hear students all the time talk about being ‘afraid’ of going to Waterloo because they feel like it’s unsafe for them,” Froyum said. “And that most certainly is not the case; that it’s unsafe for students to go to Waterloo. So we have to think about how students, as part of the community, interact with the entire community and how they talk about it.”

“My experience has been that there are lots of […] ways to make UNI a home for you and to share your diversity with the rest of UNI and the community,” Breitling said.

The Black Student Union, according to Jackson, exists to provide support to African American students.

“Stuff like this does divide us; we feel alone and separated,” Jackson said. “And we [BSU] are just here to show them, ‘We support you.’”