UNI 7: Activism impacts campus nearly half a century later

Apr 4, 2016

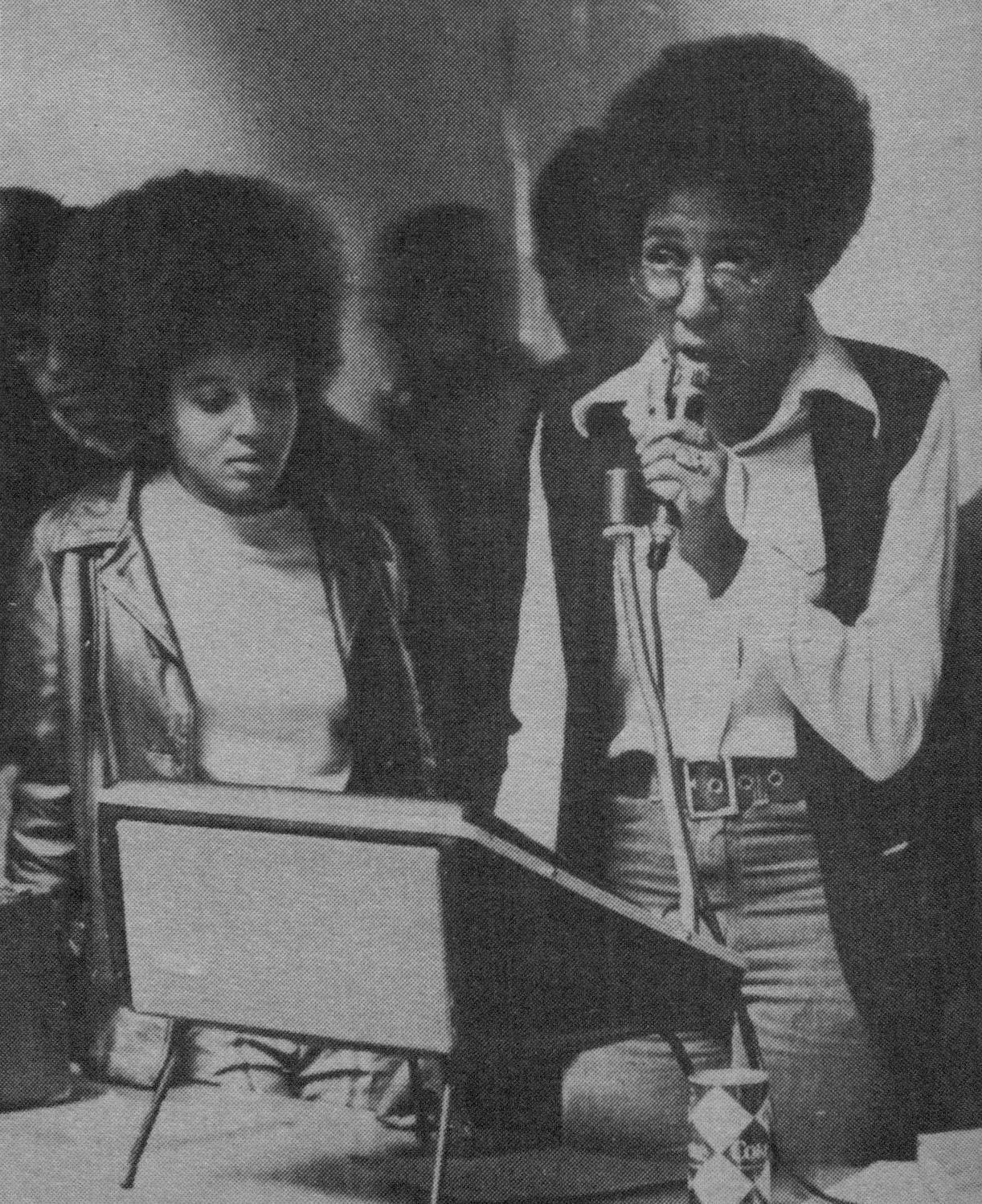

On March 16, 1970, a group of 7 students stayed the night in then-UNI President J.W. Maucker’s home, and despite being asked to leave, stayed up ordering pizzas when they got hungry. The demonstration sought a space for minority students to gather and for the administration to address hostilities minority students were facing on campus.

The sit-in and subsequent movement would lead to protests, arrests and, eventually, a space for multi-cultural students to gather.

Tony Stevens, Terry Pearson, Chip Dalton, Joe Sailor, Ann Bachman, Bryon Washington and president of the Afro-American Society (AAS) Palmer Byrd were part of this group of student protestors who would forever be infamously – or heroically – known as the UNI 7.

NISG’s director of diversity, Hansen Breitling, considers the UNI 7 to be heroes.

“We learned about them on our trip, the Chicago Connection trip, which was connecting minority students with minority alumni,” Breitling said.

Christopher J. Shackleford, a research and programming assistant at the Sullivan Brothers Iowa Veterans Museum, wrote his master’s thesis on the incident, entitled “Student activism at the University of Northern Iowa during the Maucker years (1967-1970).”

The thesis discusses the events that led to the demonstrations, beginning back in 1968, when Charles E. Quick, then-assistant history professor, proposed a reform that challenged the racial dynamics in Cedar Falls. This reform started to take shape with Maucker asking Daryl Pendergraft, who had served in a number of administrative positions, to establish the Committee on University Responsibility in Minority Group Education (COURIMGE).

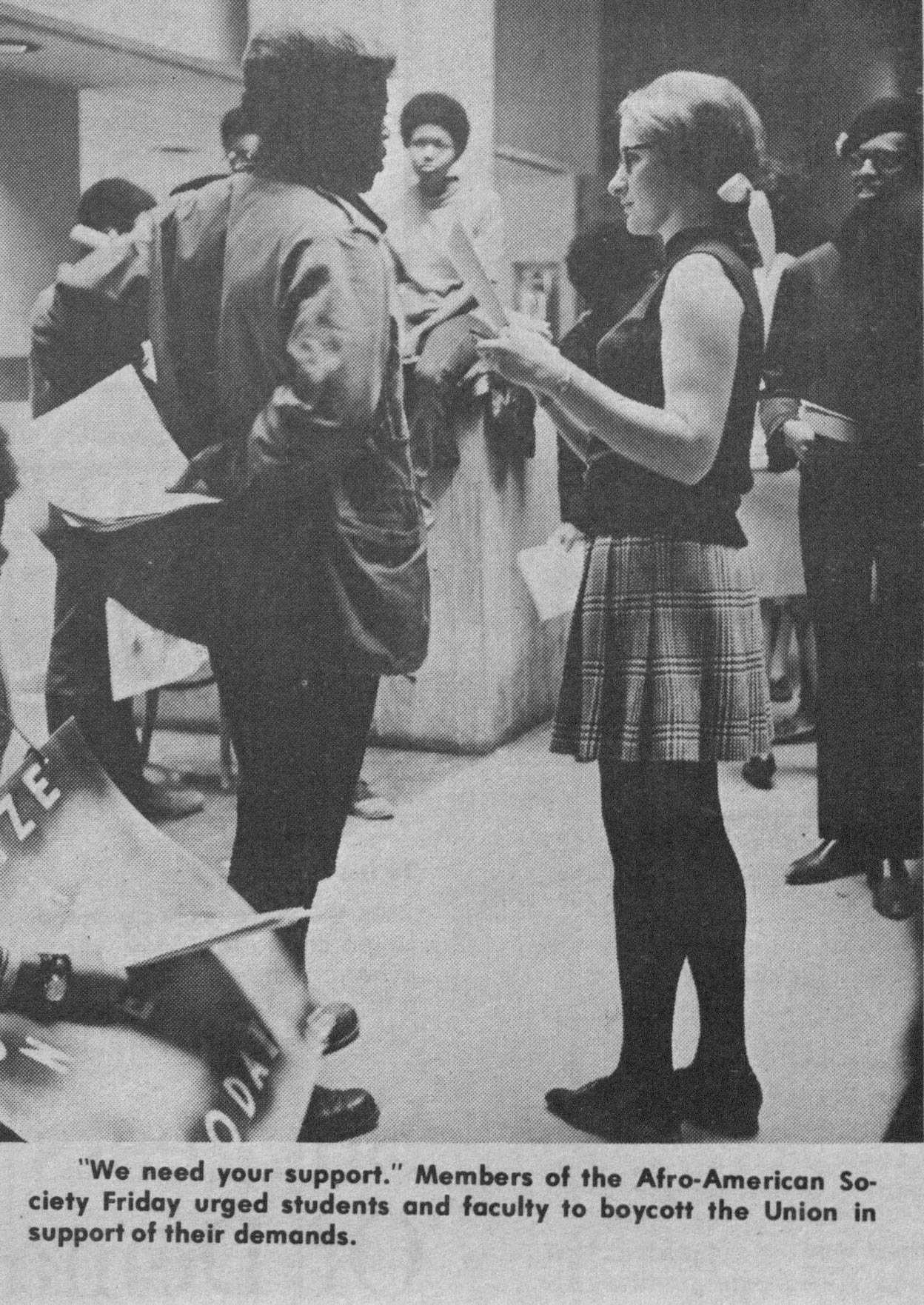

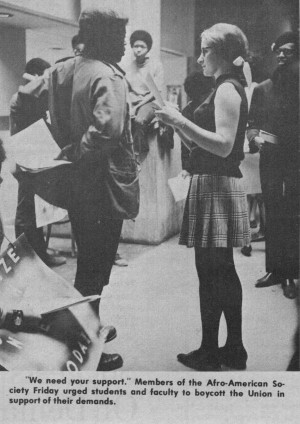

However, COURIGME struggled to implement any real changes on campus, which led to AAS to take action. William Lang, then-vice president of academic affairs, was served a list of demands from AAS on Nov. 6, 1969.

Both Lang and Pendergraft penned a history of UNI at that time period, titled “A Century of Leadership and Service.” The Lang-Pendergraft book explained in-depth how Maucker invited AAS in and had an hour-long discussion with them.

However, once it became evident that Maucker was not going to give them the decisive answer that they wished for, the situation broke down.

Maucker asked them to leave, but the students refused, spending the night and having several pizzas delivered to them as the Mauckers presumably slept upstairs.

Sailor recently commented on why he had joined the fight for the cultural center.

“Knowing that there were only 15 full-time black students spread apart all over campus,” Sailor said, “I felt a need for a place on campus to meet, come together and call it our own.”

Then-AAS president, Palmer Byrd, continues the story.

“The next morning, the word had spread that the BSU [Black Student Union] was sitting in at the President’s house and many of our white counterparts wanted to join us,” Byrd said. “Soon, parents and news outlets joined the growing protest movement. A decision was made to move the sit-in to the main administration building; so we all marched over to that building together. As the sit-in continued to grow, law enforcement agencies and campus police appeared.

“Arrangements were made between school administrators and protest leaders to resolve concerns, and the sit-in ended.,” Bryd explained.

The 17-hour sit-in lead to the UNI 7 being charged with causing a public disturbance.

This decision to take disciplinary action sparked significant student body opposition to the administration, but it was still a minority effort.

“The majority of students at that time were not supportive of our position and tactics,” said Bryon Washington, one of the UNI 7. “In retrospect, I feel my role as part of a collective helped pave the way for establishing the Black Culture House at UNI, a positive vehicle for African American survival on the campus.”

The immediate backlash on March 30, 1970 included response from student groups. The student senate requested an investigation to decide if “the due process law” had been violated and voted to hold a referendum of the student body to test their support of the Dean of Students, according to the Lang-Pendergraft book.

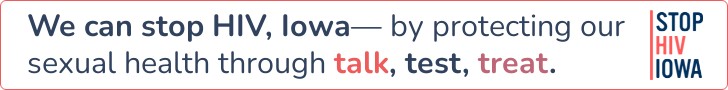

A “speak out” on student’s rights was held in the Union to an estimated crowd of 250 students and faculty. The talk led to a demonstration by about 100 students who marched from the Union to the administration building to protest the suspension of the UNI 7.

Also on March 30, 10 members of the student senate declared themselves leaders of a new Provisional Revolutionary Student Government (PRG), according to Shackelford’s thesis.

They took titles such as PRG Minister of Defense, Minister of Propaganda, Women’s Liberation Minister, Minister of Outside Agitation and Minster of Rhetorical Tricks.

This Revolutionary Government had its own list of demands, which ranged from a more responsive Dean of Students to an end to tuition and control over tenure.

The Disciplinary Committee further angered students by using a provision under their established rules in 1964 to try the UNI 7 in separate, private hearings.

On April 6, the Disciplinary Committee was meeting when about 150 students stormed the proceedings. Students who were attending an afternoon “speak-out” caught wind of the hearing and joined together to interrupt the proceedings.

The hearing was rescheduled for April 20 by the Disciplinary Committee. Precautionary measures were taken in alerting law enforcement, including Judge Blair Wood, and stationing university security officers outside building entrances by 3:45 p.m.

A speak-out after lunch in the Union turned into a protest of 50 who went at 3:30 p.m. to fill the hall and foyer outside the Board Room. The students who did not make it in by 3:45 were beating down doors, breaking glass windows and chanting profanities.

Students’ insistence to remain in the room after being told to leave led to several arrests by around 5 p.m.

Deputy Sheriff Wendall Christensen read the injunction to the protestors at 4 p.m., followed by the university attorney clarifying that anyone who didn’t leave by 4:10 would be held in contempt of court.

Nine students were initially arrested and sentenced to seven days in county jail by Judge Wood. The nine arrests were soon followed by 21 more, and ultimately 28 protestors were sentenced to a week in jail for contempt of court.

Among the students sentenced to jail time were Chip Dalton and Palmer Byrd, two UNI 7 members, along with Al Woods, a member of the Revolutionary Student Government.

Dalton recently commented to the NI about his involvement.

“Due to my strong feelings about injustices in society,” Dalton said, “I felt compelled to do my part in fighting injustice for any oppressed minority…I have been very proud of my small part in the evolution of political thought and activism at UNI.”

The entire situation seemed to have left the student body rather disillusioned by the end of the 1970 school year. The May 7 announcement of the suspension of the UNI 7 and the other indicted students who participated in the April 20 protests were met with very few rallies.

However, the full impact of the 7 can still be felt by current UNI students.

“You know, some of them didn’t ever complete a degree from UNI and were haunted by this,” Breitling said. “So absolutely, we learned how much students in the past had stood up and been willing to fight to better the university even though they might not have seen the results; so we took that as inspiration.”

Shackelford summed up his impressions on the UNI 7 phenomenon within the climate of fiery student activism.

“That’s what I think is so unique about the UNI 7,” Shackelford said, “is that for a brief moment, at least those involved in activism on campus, unified around a single cause.”