Compelling story of joy through despair

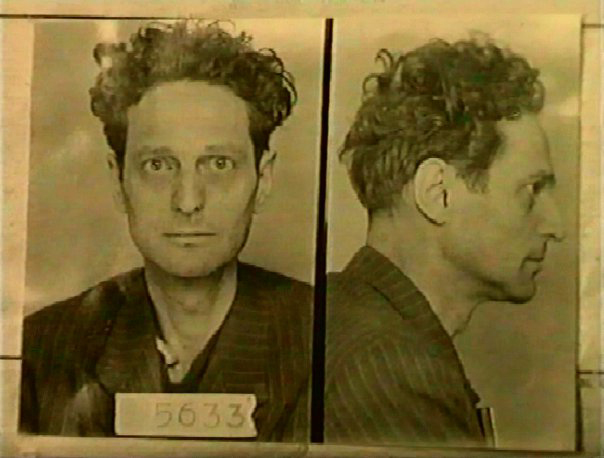

This is the mug shot of Pastor Richard Wurmbrand. He wrote the book, now movie, “Tortured for Christ” about his persecution under the Romanian communist regime.

Mar 22, 2018

The year was 1944 when the Soviet Union occupied Romania and began to establish a communist regime. The young pastor Richard Wurmbrand and his wife Sabina were among many of the religious leaders in attendance at the Congress of Cults held in 1945 by the Romanian Communist government.

As many religious leaders stood up to praise communism and pledge their support in a public nationwide broadcast, Wurmbrand and his wife were sickened because they knew communism had helped lead the persecution of the Christian community.

Wurmbrand’s wife said, “Richard, stand up and wash away this shame from the face of Christ! They are spitting in His face.” To which he replied, “If I do so, you lose your husband.”

And his wife’s response: “I don’t wish to have a coward as a husband.”

That led to Wurmbrand choosing to stand up for his beliefs on live radio in Romania, and the following two decades of their lives were spent paying daily for that decision.

Wurmbrand’s book “Tortured for Christ” tells the story of his life, and the lives of various other people in his life, including his immediate family. Wurmbrand and his wife were both imprisoned separately and tortured for their faith, but they survived long enough to be ransomed.

They went on to start Voice of the Martyrs (VOM), a nonprofit, interdenominational Christian missions organization dedicated to serving persecuted Christians around the world. VOM produced and funded the making of this movie to mark the 50th anniversary of the release of the book.

Directing: 4/5

Director John Grooters has an established number of IMDb credits for directing and producing documentary-style films. Grooters is also experienced in video shorts, which helped in keeping the pacing of the story tight and interesting. One powerful thing to note about this film is that it was all shot on location in Romania, including the prison where Wurmbrand was actually tortured.

The bulk of the movie was a successful blend of documentary and narrative. The use of close-up shots to increase the tension in scenes, such as when Wurmbrand is being tortured or is risking his life to give out bibles disguised as communist propaganda, was highly effective. The cutaways were clean, and it kept the voice over heavy story moving quickly.

The use of lighting in the film was also very well done, as the communist leaders grew in menace with darkness, but the prisoners in direct lighting appeared haggard and ever hopeful. The source lighting was excellent, and in scenes where the prisoners used their shackles to sing worship songs, the golden light from the old school lamps brought a warmth to what should’ve been a bleak scene.

And for a movie about torture, Grooters did a good job letting the audio tell the story more than sensationalizing the carnage of what occurred.

There were also many gleeful and comedic moments to lighten an otherwise bleak subject. The one shortcoming was the video before and after the movie that tried tying in the present day, because it took away from the compelling story of Wurmbrand’s life.

Writing: 4.5/5

The screenplay was written by Steve Cleary and Grooters. They took heavily from the source material and historical evidence. Grooters has well-established IMDb credits, but this appears to be one of Cleary’s first major projects.

The goal of the film was to create a narrative as close as possible to the actual events, and that was well achieved by the use of English, Romanian and Russian with the necessary subtitles. Viewers were able to feel more fully immersed when listening to Russian guards interrogate Wurmbrand.

One lighthearted scene that utilized these well is where Wurmbrand’s son and some friends go pester the Russian guards in the few Russian words they know, pleading for “gum,” “please” and “thank you” as they scurry off. Wurmbrand’s son breaks from Russian to say, “God bless you,” in English and hands a Russian soldier a flower.

The use of dialogue from the book works extremely well for the monologues. In a brutal moment, as Christian prisoners are listening to one prisoner preach (which was against prison rules), he is taken by a guard and beaten. Once the man returned, bruised and bloody, he asks where he left off in the teaching. In the following monologue Wurmbrand said, “We were happy preaching. They were happy beating us, so everyone was happy.”

The perplexing joy and smiles makes it clear in that scene none of the prisoners are the victims, but rather the victors because they had a source of joy that couldn’t be beaten out of them.

Acting: 5/5

The acting in this movie was very convincing and essential to conveying the emotional depth of the subject matter. Emil Mandanac played Wurmbrand, and his performance captured the resilience and torment of a man who would not let go of his convictions. The actor did a remarkable job immersing himself into the prisoner pastor so well that by the third act he was nearly unrecognizable to the young pastor he was in the first. The desperation displayed in his face during the scenes in solitary confinement were gripping.

But the show-stealing performance was one of another priest, who for a rough seven to 10 minute scene was beaten, hung upside down and then watched his son get beaten to death by the Russian guards. In desperation, the man cried out his compliances, but his son reminded him to never stop proclaiming the name of Jesus. The absolute devastation of the scene was so potent, it brought a deeper level of heaviness to the narrative.

The supporting actors who came and went through Wurmbrand’s perspective were essential to his story because with every sacrifice, the tension heightened for Wurmbrand and his wife. Raluca Botez did an excellent job portraying the type of strong 1940s Romanian woman who refused to let her husband stay silent even at the risk of death.

Botez’s shining scene was when the Russian secret police came for her at midnight to arrest her. In the scene, she stood tall and gracefully requested the chance to pray with her family before being taken away.

The actors did a convincing job of showing an astounding level of peace, joy and love in the face of evil. The Russian tormentors also portrayed callousness in a stark way that made it, although not easier, more believable to see them beat praying prisoners.

For a story about people who refused to let go of their convictions, the cast did a great job portraying even heavier levels of suffering as the Russian oppression grew throughout the plot.

Overall: 4.5/5

The Christian testimony is typically the story of how one came to the acceptance of Christ, but the testimony Wurmbrand told was one of how God met him throughout his suffering. In the final act of the movie as Wurmbrand lays on what should’ve been his death bed, he asked his doctor friend, a Christian hiding out in the Communist ranks, to deliever this message to his wife: “God is here.”

For Christian audiences, this movie serves as a powerful depiction of faith and the persecuted church. For more secular audiences, the film is an emotionally griping historical biopic that fully exposes the horrors communism inflicted on religious communities.

Throughout the torture, Wurmbrand expressed love for the communists while hating the communist system. The encouraging message the movie ended on from Wurmbrand was, “God will judge us not according to how much we endured, but how much we could love.”