Clothesline Project brings awareness

Oct 24, 2019

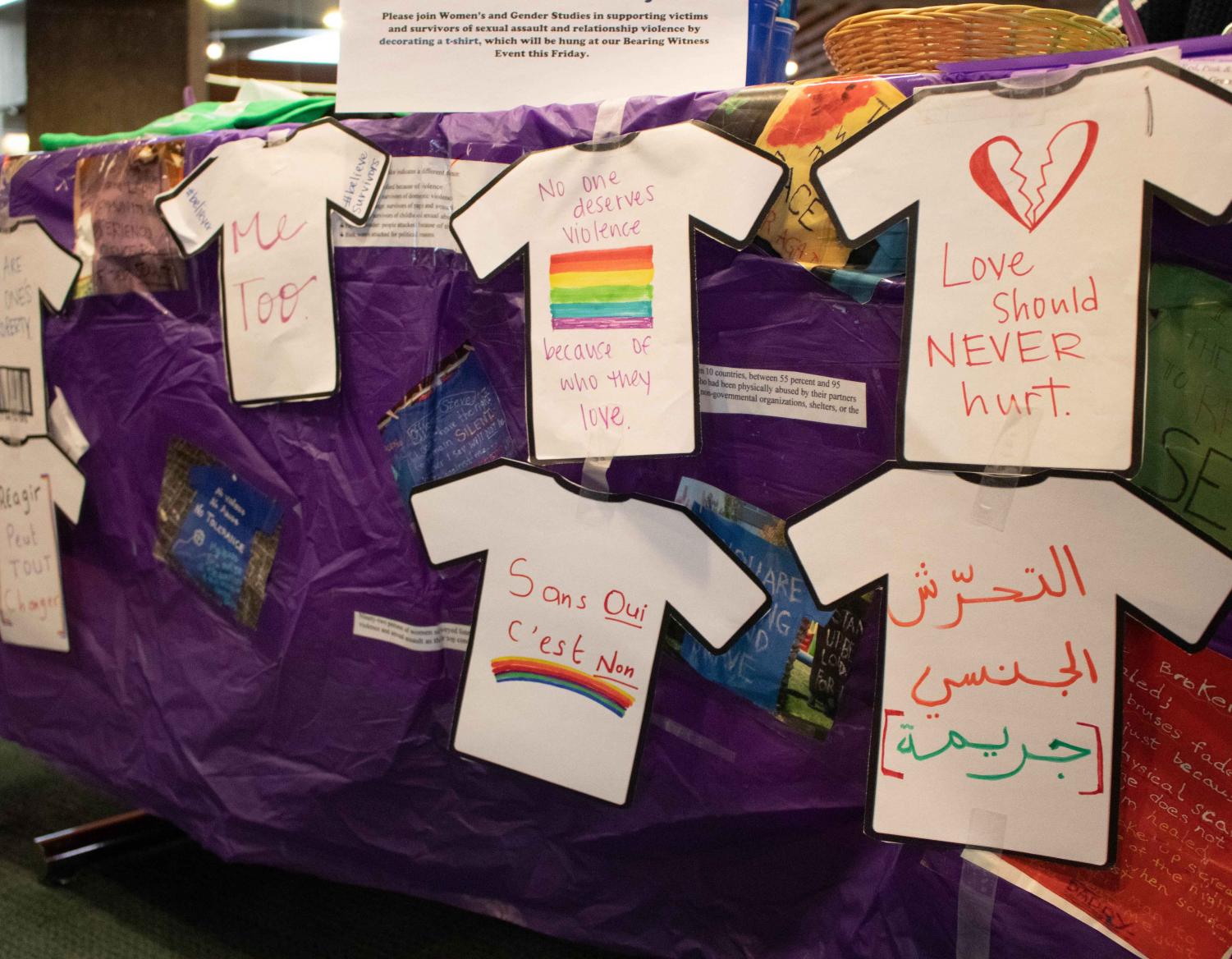

Colorful shirts will be displayed across UNI’s campus on Friday, Oct. 25 as part of the Clothesline Project, an interactive event that visually represents violence that occurs within communities, both noticeable and hidden.

“The history of the Clothesline Project originally started out as a representation of violence against women, hence the clothesline since doing laundry was seen as a woman’s job and issue,” said Sara Naughton, a second-year graduate programming assistant for Women’s and Gender Studies. “It has evolved now to represent violence against all marginalized populations. That includes minorities and the LGBTQ community.”

The event is happening in conjunction with Relationship Violence Awareness Month. Shirt-decorating events took place from Oct. 21 through 23, with participants able to share either their personal experiences or those of friends and family members.

The messages that will be displayed during Friday’s “Bearing Witness” event will vary between support, anger and confusion around relationship and gender violence.

The Clothesline Project began in 1990 in Hyannis, Massachusetts, according to its website. The program has gone on since 2014 at UNI. As more shirts are created, shirts from previous years are hung up in Sabin Hall. The Clothesline Project is a global project in which several schools and communities participate.

As she has continued to work with the program, Naugthon has found the stories that she’s heard to be motivating.

“I always find it inspiring when people are at the point in their healing as survivors that they feel comfortable enough to put their story on a shirt,” Naughton said. “That’s a very public thing to do. I don’t think that it’s necessary for all survivors to get there, and some never do. But I have found that in the past year that has been a really inspiring part of it — when survivors are willing to hand over the shirt and say, ‘This is my story; I don’t mind if you share it with others. I want my story to help someone else.’ We keep those shirts, so that t-shirt will last and last for as many years as we do the Clothesline Project.”

While the overall purpose hasn’t changed since the project was brought to UNI, Naughton mentioned that the definition of gender violence has expanded to include different races, immigration and refugee statuses and sexual orientations.

In addition, while the overall purpose of the project hasn’t been altered, Naughton believes that its scope has. The colors of the shirts are meant to have various meanings. Due to instances of sexual violence on UNI’s campus, many of the shirts are yellow, orange or pink, representing sexual violence against women.

Although she sees the Clothesline Project as a great way to spread positive messages, Naughton has still encountered challenges with the program.

“There’s an attitude nationwide, but especially in Iowa, that tends to look at issues like sexual violence, assault and rape and say, ‘That’s not my problem, so I’m not going to do anything about it,’ she said. “That’s not to place blame on people who feel that way; I think that that’s an attitude that’s pretty socialized. We’re kind of taught to feel that way.”

Naughton said one of the struggles faced regarding the Clothesline Project and similar events is the lack of student participation.

“We’re working to rectify that in different ways,” she said, “but I don’t think that’s unique to the UNI campus; it’s an issue that a lot of activists and advocates face.”

Overall, Naughton emphasized that violence, rape and assault do happen in this community. She also said that support and advocacy exist for those who need it.

“I feel like it’s everybody’s business, but people still aren’t aware,” said Lamis Laouar, a second-year grad student in Women’s and Gender Studies. “People think that it doesn’t affect them and their family. If it’s not affecting my family, then I’m staying away from that.

“I wish that I could see it in my home country of Algeria, like why not take it there?” Laouar continued. “I’m trying to call my friends from different countries and I want them to stop by to remember that these things happen all the time. I want to do something like that in Algeria when I go back next year.”