‘Burkini’ part of unrealistic standard

Sep 8, 2016

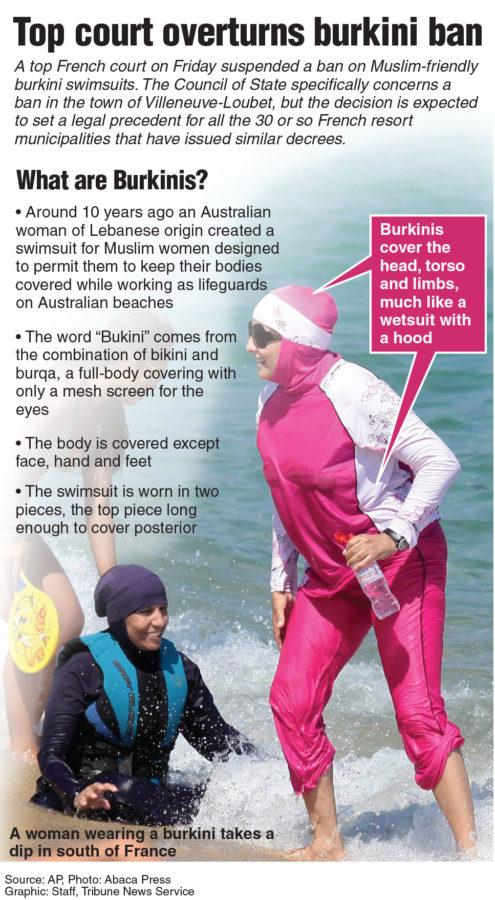

By now, you’ve probably heard something or another about the “burkini” and the banning of it by European localities, especially in France. Chances are you’ve seen the viral clip of four armed French police officers forcing a Muslim woman (and apparent third-generation French citizen) to remove part of her elaborate swimming garb in order to comply.

The New York Times reported that at least 20 cities along the Mediterranean coast have enacted such bans, and so far the bans in France have been largely upheld by French courts (the ruling of the Council of State notwithstanding). What you probably don’t know is how much deeper this public posture goes.

There is a political principle called laïcité (translated literally as “secularism” in English) under which the French have operated since their Revolution. This principle, expressed in the first article of the French constitution, necessitates the removal of all religious references from public life, especially in the daily operations of government.

French elected officials do not make proclamations like Iowa’s Governor Terry Branstad recently did regarding the study of the Bible. The input of religious folks is generally considered incompatible with reasoned political debate, and so French politicians rarely, if ever, speak of their faith, much less cite it as a reason for anything they believe and fight for in politics.

If you’re an antireligious bigot, or a rather secular person, or even on the political left generally, this may sound appealing to you. It may appear to be a welcome change in course from the days of theocracy and establishment of state religions. In fact, a popular English term used to describe laïcité happens to be “separation of church and state.”

However, the “burkini” ban, and the banning of face-covering garments in all of France since 2010 (which was upheld by the European Court of Human Rights), are not mere accidents of French bigotry and xenophobia (although those no doubt play a role). “Separation of church and state” has really meant “separation of religious life and public life” in France.

If the people of France decided to be consistent and mandate all religious garb not be worn in public spaces (including the famous garb of Catholic nuns, known as the “habit”), they would probably get away with it. That is the natural, logical extension of French laïcité, wherein religion is regarded as a purely private affair and publicly expressed devotion to one’s faith is frowned upon on the grounds of being, in the recent words of these French cities, “[dis]respectful of good morals and of secularism.”

Those of you in your second year at UNI may recall my column last semester in which I defended the recent revival of religious freedom laws in the U.S. I reminded you then that religion is not a mere habit appropriate in certain contexts and not others, but rather an essential force that makes intellectual and behavioral demands upon every single aspect of a religious person’s life.

French laïcité flouts this reality. It demands its citizens, in the recent words of Veery Huleatt, choose between being French or being Muslim, and that can (and for consistency’s sake, should) apply to other faiths just as easily. In other words, French laïcité is an impossible standard.

Fortunately, the U.S. has never operated under anything like French laïcité. Rather, the First Amendment to our Constitution has mandated two key doctrines: state disestablishment of religion and free exercise of religion. These combined principles have worked to be inclusive of religious people in public life while neither empowering them to impose particular religious doctrine on unwilling citizens nor requiring that they check their religion at the door.

Even from America’s inception, there were Christian leaders (specifically the Baptist preacher John Leland) who made it clear that their ideal of religious liberty applied to Muslims as well, despite the fact that there was apparently no Muslim population in the young United States. Clearly, the U.S. has failed to meet this standard at many points (just ask the Mormons and the Jehovah’s Witnesses), but this has nevertheless always been the intent, and where it has been consistently applied, it has worked well.

Nevertheless, there is a dissatisfaction of increasing volume among select segments of the American population with this policy. For some reason, some U.S. citizens seem more vocally uncomfortable with and even hostile to religious expression that takes place anywhere outside of the walls of one’s home or one’s church. I even know of a woman from my undergraduate alma mater who has expressed a desire to amend the Constitution to clearly, decisively demand the “separation of church and state.” To these people, I point to France and ask, “Is this what you want?”