Bad studies don’t help rape victims

Mar 30, 2017

I am continually surprised and saddened by the number of people, particularly women, in my life who have been sexually assaulted. From fellow undergraduate alumni to friends from church to new friends I’ve made in my short graduate studies here at UNI, so many have been affected by this in one way or another.

Especially as a happily married man, I don’t understand the very desire to force others into participation in sexual activity, much less the mental gymnastics it takes to justify actually following through on such desires. I see it as a horrific, barbaric crime that must be met with the fullest force of the law wherever it is found, and steps ought to be taken by individuals and institutions outside of the justice system to lessen its frequency and effects on the lives of innocents.

That is why I cannot abide most sexual assault awareness campaigns. It is abundantly clear to me that most of them are not primarily about addressing sexual assault but are rather making the campaign participants feel better about themselves. Rather, these campaigns are routinely based upon half-truths, exaggerations and even outright lies about sexual assault.

Focusing on campus rape specifically, the now-infamous assertion that “one-in-five college women will be sexually assaulted” is just not true. If it were true, as Emily Yoffe pointed out in Slate, that would mean that many US university campuses are as dangerous as the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where rape was used as a weapon of war. Does anyone actually believe this to be true of any American college campus?

So why does this figure go flying around public discourse, including in the Student Wellness Services’ article in the Northern Iowan last Monday? Because it’s arrived at by studies that are almost universally based upon terrible survey methodology, with the usual suspects being vaguely or badly worded questions and low response rates from self-selected, non-representative samples.

The bad questions will ask respondents about things like unwanted kissing and even whether they had been told false promises as a means of getting them to consent to sex. While unconscionable and violating, these behaviors simply do not meet any legal or rational standard of “sexual assault,” and are unfortunately included in calculations like the “one-in-five” figure.

Because they are included, “false promises” and “unwanted kissing” rhetorically become “sexual assault” and then “rape” in the minds of average people, who lack either the time, capacity or inclination to read these awful studies themselves and understand what they really mean.

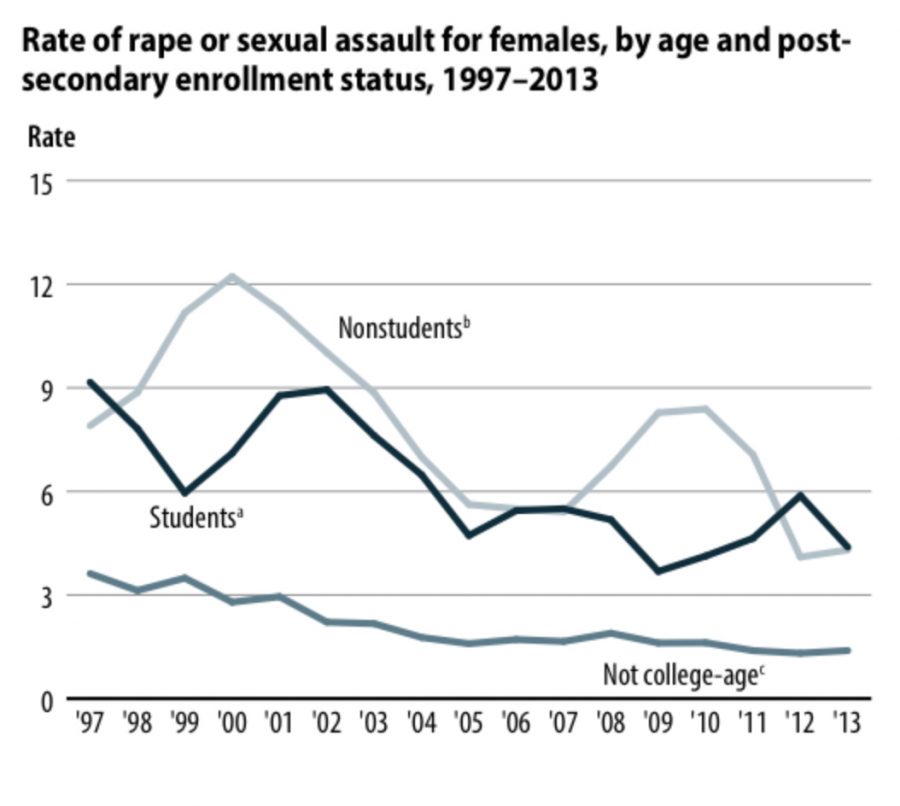

The most reliable estimates come from the Bureau of Justice Statistics in the US Department of Justice, who put the figure for college women being victims of sexual assault is not one-in-five, one-in-10, one-in-25: it’s one-in-53.

By claiming “one-in-five,” the feminist activists and gender advocates are literally blowing up the problem to be more than 10 times greater than it actually is. In fact, that figure is a 16-year-low, with campus sexual assault going nowhere but down.

One rape is too many. But one in 53 is a serious problem, not a crisis, and certainly not an epidemic. But this perception of epidemic-level severity (propelled by this and other myths about sexual assault) skews our perspective of the problem and causes us to pursue heavy-handed, misguided and just plain wrong means to combat it.

From mandatory consent training to kangaroo courts in which the accused is guilty until proven innocent even to the point where male victims of sexual assault are expelled purely on the word of their female accusers (looking at you, Drake University), we are pursuing awful solutions to a manufactured crisis.

So, as March warms into April, for the sake of my friends and all other victims, I ask you all to take up the challenge urged by the activists behind Sexual Assault Awareness Month: educate yourself. Do what you can to learn about the reality of sexual assault as it is, not as the activists want you to think it is. Don’t be content with feel-good halfway measures that only support your own moral narcissism.

Think critically about the sociologically-established link between sexual assault and alcohol consumption. Support measures that both enhance security for victims and preserve due process, and oppose those measures that fail to do either.

Britt Griffin • Apr 3, 2017 at 7:20 pm

Want to know why sexual assault (which yes includes a spectrum of different violating behaviors, mainly any sexual act that takes place in the absence of consent or presence of coercion) is an epidemic and public health problem? Because people like Kyle construct rape culture by minimizing sexual assault, blaming victims, and protecting perpetrators instead of believing survivors, understanding the barriers to reporting, understanding that for every 100 occurrences of rape, only 3 rapists will spend even a day in jail, and recognizing the seriousness of any sexual assault, not just assault that meets legal criteria for rape, for our survivors and our communities.

I am astounded and infuriated that a college publication would allow this triggering, minimizing, revictimizing, victim-blaming, rapist-protecting travesty of an article to be published. Kyle’s the one that needs to educate himself. UNI needs to apologize to the community and survivors that have to suffer again because people can publish stuff like this as if its normal, okay and factual.

Issue a retraction and an apology!

Gwen Bramlet-Hecker • Mar 31, 2017 at 10:50 am

The Bureau of Justice Statistics report data about the crime of “sexual assault” as defined in statute. It is a measure of the activity of the agencies within the criminal justice system — the police, the courts- and the number of cases known to them and to which they spend time and attention. . They are very useful in understanding trends in the system’s activity surrounding sexual-related crimes, but are not — and the BJS would agree – a true measure of the behaviors encompassed in the spectrum of sexual violence.

This spectrum does in fact include forced kissing, touching, groping, all the things women experience far too often – sexual activity perpetrated on them without their consent. (Those things too are included in the statutes outlining sex-related crimes) Most women. Almost all women. Ever wonder why women actually go to the restroom in pairs? Because of the inherent vulnerability they feel always caused by what they, and their friends, sisters, mothers, and acquaintances, have experienced.

Using BJS statistics to make the arguments in this piece is inappropriate, an “apples to oranges’ comparison, therefore rendering the stated arguments invalid. BJS, and the data gathered, would, however, be a fine place to start looking if one wanted to see how rare false reporting of sexual assault really is.

Ana Kogl • Mar 31, 2017 at 9:57 am

I’m confused about what the basic argument is here. Is it that we have become hysterical about rape on college campuses, and as a result are engaged in a witch hunt against accused rapists? Is it that we are causing unjust and unnecessary suffering among the accused through “kangaroo court” trials that lead to expulsions? Is the basic argument that we are too sympathetic to those who go to authorities to report sexual assault, and not sympathetic enough to those accused of sexual assault? I for one would be interested in seeing evidence for this on UNI’s campus.

Christen • Mar 31, 2017 at 8:02 am

The Justice department is looking those convicted. How many do you believe go unconvicted because the only proof the women has is her own voice? How many men stay silent because there is no DNA that a women raped him because he was so confused he showered? How many victims stay silent of their sexual assaults because it is was not rape and there is no DNA that they were touched against their will? How many people are you silencing with your words against a campaign that is not fear mongering but challenge society and people like you that silence survivors. Shame on you. You have idea what it is to be a survivor or be a women who has been assaulted. I’m sure if you could see into everyone’s mind you would pull your head out of your cloud of “I would never hurt someone so why would anyone else” butt because everyone is like you. There are bad men and women who hurt people!!! Just because you say you’re not one doesn’t mean you should demean the education of those who don’t know what assault or consent is because no one has taught them!

Jeremy Everett • Mar 30, 2017 at 9:49 pm

Calling survivors of sexual violence “victims” only goes to show how hypocritical this is. I like how you prefaced your rant with what is basically an extended version of the go-to “I’m not ____ but…” and went directly to insulting the people actually trying to stop sexual assault. ”

Make them feel better about themselves.” Do I need to go into how this hurts your credibility? You clearly lack the empathy to assert yourself as some sort of authority on the subject. Even if I agreed with what you have to say (I certainly don’t), you’re off to a bad start.

One and five… Okay, you can’t say “if that were true” and follow it up with that backwards justification. That whole paragraph is a mess, dude. It’s like me saying, “People named Kyle have an arm growing from their forehead, but if that were true, as my friend pointed out on Facebook, he would need three gloves in the winter!” Yes. Yes, they would. Perhaps not the best analogy or whatever, but I’m typing this on my phone with 12% battery left and need to hurry. Oh, to answer your question: Yes.

Do not minimize unwanted kissing or manipulation like you are doing. I’m pretty sure if I walked up to you and forced my Taco Bell-covered tongue into the back of your throat you’d be upset, too. You may even claim I assaulted you in a sexual manner. Moving on..

Kyle, good lord almighty- the mind of an “average” person? I may be a poor simpleton with no high horse to ride, but it doesn’t take genius to notice the arrogance drooling from this entire column.

1 in 53… Sir, the word you’re looking for is “figuratively” blowing up the problem. As the self-proclaimed hero of academia, I think it’s weird you wouldn’t think about the prevalence of sexual assault in relation to the population in the study. 1-in-5 could be a correct generalization in that area. And since the DOJ info is national (I assume they didn’t do their own study on that campus), it would be fair to say that a current epidemic of sexual violence could be occurring in that area.

Mandatory consent… Considering 1 out of 6 rape or attempted rape survivors are women and 1 in 33 rape or attempted rape survivors are men (RAINN), I think some gentlemen need a good talking to. Anyway, most guys don’t have to carry pepper spray on their keychains because simply having a penis puts them at risk of physical and sexual violence. Also, I could say same thing about the courts making mistakes (looking at you Stanford University’s Brock Turner).

So, as March warms into April, for the sake of my friends and all other survivors, I ask you to take up the challenge urged by the activists behind Sexual Assault Awareness Month: educate yourself.

P.S. Can anyone submit something to the Northern Iowan and get it shared out like this or is there someone who filters through the garbage?

Miciah Carter • Apr 1, 2017 at 2:05 pm

As someone who knows Kyle personally your response is disrespectful and insulting. Your comment is full of emotional bias and personal attacks. Those should be left out of the conversation. Onto the article itself, take and unwanted sexual advances are two separate things because one is socially unacceptable and the other will get you time in jail as long as your name isn’t Rapist Brock Turner. The justice system doesn’t catch every criminal in fact it was made to avoid condemning the innocent by presupposing their innocence. The burden of proof falls on the accuser and unfortunately it’s extremely hard to prove sexual assault especially since many victims don’t come forward right away. As to victims or survivors why not either or? I don’t see why it’s wrong to call someone who has been assaulted a victim. He’s right about the statistics though, many so called studies are framed to get the result that the researchers are looking for. It’s important to be conscious of how a study is conducted before deciding whether or not it is a reliable study. We don’t need fake statistics to help raise awareness about rape just like we don’t need fake accusations of rape (see mattress girl, Lena Dunham and others).