Low-skilled labor plagues some grads

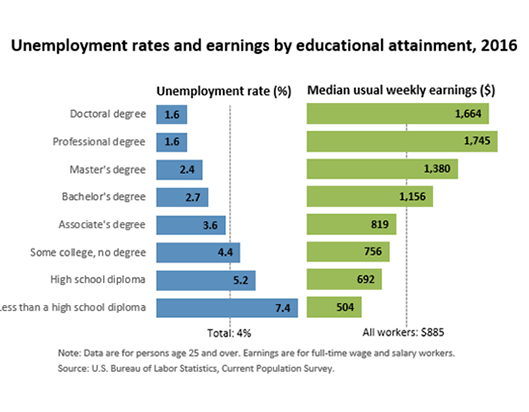

Unemployment rates decrease steadily with increased education, but low-skilled employment remains a part of employment statistics that can be deceiving.

Oct 5, 2017

An image that has become prevalent in the United States since the Great Recession is that of a college graduate, often saddled with tens-of-thousands of dollars of debt, working as a coffee-shop barista. Stories of college graduates working low-paying jobs for which they are clearly overqualified has been a frequent topic of news stories and online articles across the country.

However, the frequency at which college graduates find themselves working in these low-skilled, low-wage jobs is lower than seemingly perceived.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, nationwide, about 12.6 percent of college graduates aged 22 or 23 with a bachelor’s degree are working a low-skilled service job, which includes but is not limited to: baristas, waiters and waitresses, bartenders, cooks, retail store sales clerks and cashiers.

Many college graduates who work low-skilled jobs to make ends meet after graduation often move onto better jobs; just 6.6 percent of graduates aged 26 to 27 were still working a low-skilled job.

A student’s odds of working a low-skilled job after receiving their college degree varies significantly based on their major.

According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the probability of working a low-skilled service job among recent college graduates was highest among those with majors Leisure and Hospitality, 23.4 percent, Performing Arts, 20.6 percent, Fine Arts, 16.5 percent and Anthropology, 15.5 percent.

The degrees with the lowest rates of graduates working low-skilled jobs were variations of engineering degrees, which all had a less than 2.5 percent rate of graduates working low-skilled jobs, followed by Nursing, 2.5 percent, Construction Services, 2.5 percent and Business Analytics degree holders, 2.5 percent.

According to Matthew Nuese, associate director of Career Services, being stuck in low-skilled service jobs is not always a black or white issue. Career Services assists students in their prospective career paths and keeps track of the fate of UNI students after they graduate via survey.

“If they’re in a job that is developmental or a low-skilled job, we count that percent as ‘still seeking,’” Nuese said. “So if you took a job as a sales clerk at a retail store, and you have a bachelor’s degree in political science, we’d count that as still seeking employment.”

According to Nuese, Career Services is able to keep track of where most UNI graduates end up soon after graduation. An annual report published by Career Services, the most recently of which was created in 2016 and published Jan. 1 of this year, was able to track down 86 percent of recent graduates to see where they were on their career paths.

The Career Services report stated that 78 percent of recent UNI graduates were employed full-time, 12 percent continued their education, 3 percent were employed part-time, 5 percent were still seeking (including UNI graduates working low-skilled jobs), greater than 1 percent joined the military and 1 percent were classified as “other, not seeking.” The report surveyed UNI graduates from the classes of August 2015, December 2015 and May 2016.

UNI graduates that were working part-time or were in the still seeking category made up 8 percent of the respondents.

According to Nuese, most UNI graduates are on a career path that they are satisfied with.

“Roughly 88 percent of our students indicated that they were satisfied with their career progression,” Nuese said.

When asked about the 6.6 percent of college graduates nationwide that were still working low-skilled service jobs at ages 26 or 27, Nuese said that there are some students who have their own struggles keeping work.

“They are probably people that have significant challenges to maintain work,” Nuese said. “They might have a felony, they might have an addiction. Some of it might be as simple as they’re caregivers, or if you’re living in an economically deprived area, and there’s just no jobs, then you’re kinda stuck unless you wanna relocate. But it still costs money to relocate.

“If you bought a house, and you can’t sell your house, you’re stuck there, because of all of your investments there, and you literally have no money in your name to move because it’s typically two to four thousand dollars to move somewhere else, and so that portion [the 6.6 percent] will likely always be there.”

Nuese outlined several steps students can take to beef up their resume for employers to ensure they are on a career path they are satisfied with after graduation.

“What we provide is an understanding of what the world will be like. We give you contacts and a network in context to understand: here’s where you could go,” Nuese said. “The one thing that will always help you is more experience, broader experience… that’s why we feed you these opportunities to have that happen.”

Nuese stated that the best thing students can do to improve their post-graduation prospects is getting experience in their field through internships, field experiences and student teaching.

When describing what employers look for in students, Neuse referenced a document from the National Association of Colleges and Employers that contained survey results of attributes employers look for most in college graduates.

The top attributes were major, leadership, extracurricular activities, GPA, ability to work on a team and communication skills.

While many college graduates find themselves working jobs they are vastly overqualified for and that do not pay enough, according to Nuese, students can take steps to increase their chances of landing on a career path with which they are satisfied.

The first such step is often just knowing what ones wants to do when one graduates.

“The student that doesn’t know what they want will almost always end up somewhere they don’t want to be,” Nuese said.