Recycling changes coming to campus

Apr 15, 2019

With Earth Day just one week away, environmental concerns are blossoming on campus. UNI community members may have noticed that the campus recycling protocol is changing.

According to UNI Director of Sustainability Eric O’Brien, the changes are the result of several related factors in the structure of the United States’ recycling system. The great majority of recycled material in the United States is not processed domestically, but is shipped overseas, mainly to China, a fact which O’Brien said may be startling for some students and citizens.

“We haven’t built the industry at a large scale to be able to handle our recyclables domestically,” he said. “We built a system where we’re not thinking about where it goes. We recycle it and we just feel better about the fact that it’s being recycled. We don’t realize it’s all going to China and that we don’t re-use the majority of it here locally.”

However, about 18 months ago, China began imposing tighter restrictions for contamination levels in the recycled materials it will accept. According to O’Brien, the old standard called for approximately 80 percent of material in a load to be clean, or uncontaminated. That number has now increased to 99.5 percent.

“Basically, if there’s anything that is contamination in our waste stream,” he said, “our service provider will reject our entire load from the whole university.”

Contamination of a load can occur in several ways, according to O’Brien. The most obvious comes from garbage or other clearly non-recyclable products. However, contamination also occurs when individuals recycle objects which appear to be recyclable — or may even be labeled as such— but aren’t acceptable in a single-stream recycling program.

“People saying ‘Well, this pizza box is cardboard, so it is recyclable,’ but it’s covered in grease,” O’Brien said. “If there’s food waste on the material, that would be considered contamination. And things like plastic bags might be a recyclable plastic, but they cause major problems in the recycling stream. They will wrap around the machines and bring the whole thing to a stop.”

Whatever the way in which a load of recycling becomes contaminated, the tightened restrictions from China have slowly trickled down to affect citizens here in the United States. Like many communities and campuses, UNI sells most of its recycling to a local service provider; in this case, the university’s provider is in Cedar Rapids. The service provider then handles the transaction with overseas centers in countries such as China. Thus, the service providers were the first to experience the effects of the change in regulations.

“Throughout this academic year, we at the Office of Sustainability have been talking about ways we could change our system, knowing full well that we would roll something different out for the 2019-2020 school year,” O’Brien said. “Then the service provider made a change based on their company policies and said, ‘Things have to change now.’”

The biggest change for current UNI students, especially those who live in the dorms, is that, beginning immediately, students must not place their recycling into the campus dumpsters in plastic bags.

Previously, O’Brien said, the Cedar Rapids service provider had specifically requested that the campus use bags so that contaminated bags could be individually removed without rejecting an entire load of recycling. But now, the new regulations mean that any loads of recycling with plastic bags will not be accepted. Students should instead place recyclable products loosely into the recycling dumpsters.

For many UNI students, this won’t be a drastic change in their current recycling habits. Nick Steffens, a freshman digital media production major who lives in Campbell Hall, says he never used a plastic bag for his on-campus recycling simply because his hometown recycling program didn’t use them.

The new elimination of plastic bags might not be such a radical behavior change for students. However, what might be a bigger behavior change is the reduction of what O’Brien terms “wish-cycling,” or placing an item in the recycling stream even if citizens are not completely sure it is recyclable, in the hopes that it is. Wish-cycling is a common practice and an example of “good intentions gone bad,” according to O’Brien.

“If you look at something and you don’t know for certain that it’s recyclable, it’s better to put it into the trash,” he said. If the item turns out to have been recyclable, “it’s one recyclable item that made its way into the landfill. But on the other side, if it is something that’s not recyclable and they throw it into the recycling stream, it has the potential to cause an entire week’s worth of recycling from UNI to be rejected and end up in the landfill.”

Plastic food containers from on-campus retail stores, for example, can theoretically be recycled, but must be completely clean and dry, something which O’Brien says is almost impossible with containers which have held salads and other food residue. If unsure, students are better off throwing it into the trash, he said.

O’Brien said that decreasing wish-cycling is a “behavior change” that will take time, but one that needs to take place on campus and in communities nationwide. This is an issue in flux, and the current changes to the campus recycling program will likely not be the last.

“Right now, we’re trying to address [the changes] without a lot of extra burden on the students, faculty and staff for the remainder of the school year, but we do know things are going to look different next year,” he said.

Regardless of the future for the recycling program, students can ensure that the UNI campus is able to continue recycling by making the necessary changes and following the new guidelines.

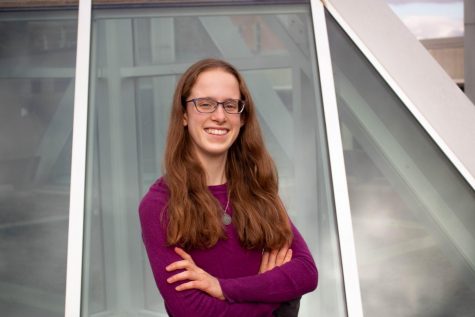

“We are a big campus and we do make such a decent-sized portion of the Cedar Valley community, so if we don’t recycle, that’s just going to cause more damage to the Earth, especially when there’s really no more space for landfills,” said Kristina Huling, a junior public relations major who lives in Panther Village. “I think it’s pretty important for us to actually listen to those emails and actually do what they’re saying.”