Tales of the Bulgarian Rose

Nov 10, 2022

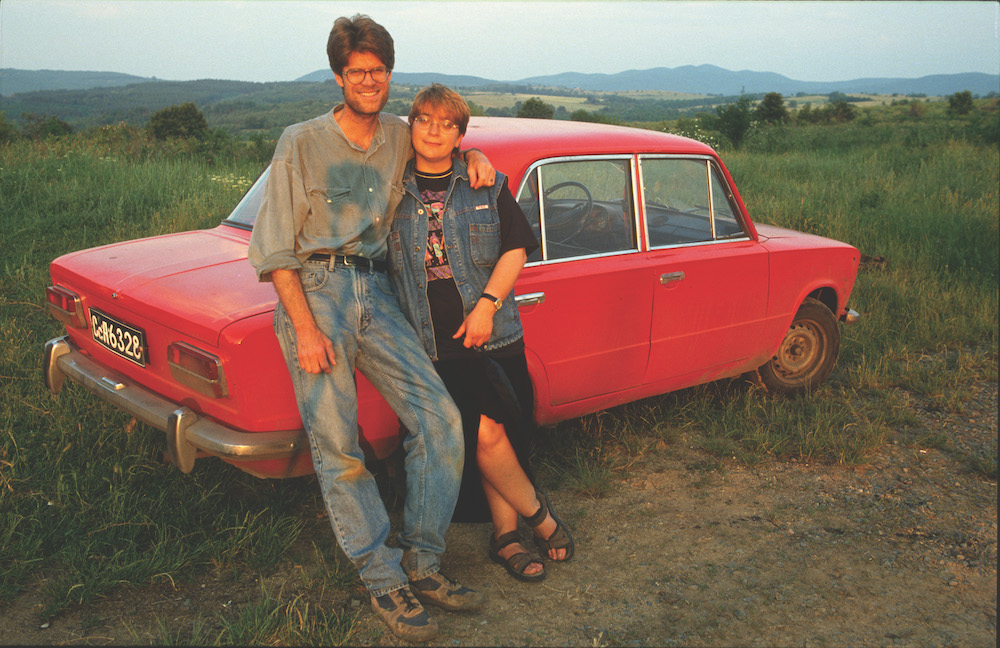

On the second level of Rod Library on the art wall hang 15 freshly printed photographs taken by journalistic professors Rick Truax and Anelia Dimitrova, Ph.D., who also serves as an advisor for the Northern Iowan. The photo story “Tales of the Bulgarian Rose” includes a total of 33 photos and serves as a memory snapshot of their 1997 trip to Bulgaria after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Their purpose was to document the rose industry after the rise of democracy in the country. The images will be showcased in Rod Library until January when they will be moved to the Hearst Center For the Arts.

They knew they would be covering the story of the rose before they even boarded the plane. “It’s one of the treasured, iconic products of Bulgaria. The oil of the rose is more expensive than gold. It’s one of the things Bulgaria has for centuries prided itself on,” Dimitrova says. Having grown up in Bulgaria herself, she was familiar with the rose industry and wanted to share where she grew up with Truax, her husband.

Harvesting rose oil is a very intense and laborious process. The picking season is short, lasting for only the month of June. Workers have to wake up in the early hours to pick roses before the morning dew evaporates, filling their bags to the brim with these flowers only to produce a thimble of oil. The oil harvested from the roses is used in the finest perfumes in the world.

“It was a very tumultuous year in time. The Berlin wall had just fallen eight years earlier. Eight years is nothing for history,” Dimitrova says. Everything in these people’s lives had tumbled down. Prior to the fall of communism, agriculture was collectivized in Bulgaria and owned by the state. When they began their journey of telling the story of the rose in ‘97, farms were abandoned and ownership was unclear. “There were a lot of people, especially older people, harkening after communist times,” she said. “Everything was orderly, they didn’t have any ownership or property, but the state took care of everything. And now they could see that democracy can be disheveled.”

In fact, after all these years Truax learned that ‘97 was when the rose industry in Bulgaria had “literally hit its worst point.” Fortunately, the country has rebounded and is currently as strong as it’s ever been.

Twenty-five years later, this story comes to life for the first time. Truax can’t remember when the inspiration struck to make it an exhibit, but assumes it started when his favorite picture fell off the wall of their home and broke. The image is of four young women in traditional dress at the rose festival. Seeing the broken picture sitting in their basement Truax says, “I was so ashamed that I hadn’t fixed it up and put it back on the wall.” About a year and a half ago, Truax took the picture and got it reframed, thus inspiring a motion to print about 15 pictures and show them somewhere. What surprised him was that at the end of the summer, he had 33 stunningly important images.

Dimitrova says, “working on this project had a life sustaining role during the pandemic, with how we were all isolated. The timing was perfect…working on this reconnected us with our younger selves 25 years ago. It also helped keep up that interest and sustain interest in our work.”

Dimitrova highlights that although she feels pride now that the photo story is published, most of all she feels a great sense of nostalgia. Truax and Dimitrova had only been married for a year before flying out to Bulgaria. In fact, Truax’s uncle gave a large cash gift for their wedding present that they saved and helped fund the trip with. UNI also gave Dimitrova a small summer grant towards the project. She says, “It was very important that at the time we didn’t have any money and it was a nice little gift and a vote of confidence that we should do something that is meaningful.”

When looking back on the time spent in Bulgaria those 25 years ago, Dimitrova says, “The most important thing is being a witness to something…It’s almost like you are a time capsule, because you capture a moment in time. Every single one of these images is immeasurably valuable because it cannot be repeated.”